The chances of Anning (1799 – 1847), the child of a cabinet-maker, succeeding as a fossil finder and palaeontologist were slim. Anning was an uneducated woman from a lower-class background who was also a dissenter. However, she was so intelligent, curious, and passionate that she is well known today for her findings. Pierce (2013, p. 19) comments that Anning was generous with her knowledge and experience, and shared this with “the eminent gentlemen scholars who came to visit her. Inevitably, they were not always so generous in giving her the credit she deserved, and she became somewhat bitter as they took freely of her work, discoveries and ideas and presented them as their own, seemingly without a second thought, while she continued to live a hard life all her days.” Despite this, today Anning is well-known and celebrated for the significant role she played in the history of fossils of primarily the Jurassic period.

The French Revolution affected travel to Europe, resulting in Lyme Regis becoming a popular holiday destination. Many local people sold fossils to the visitors, and Anning sold her fossils to casual tourists as well as those who took a more scientific interest. Anning’s father took his children on trips to find fossils to supplement their income. After his death, Anning and her brother continued the search for fossils.

Anning found her first fossil in Lyme Regis at the age of 12 years old. It was the first complete skeleton of an Ichthyosaurus (renamed Temnodontosaurus platyodon). Mary’s brother Joseph found the head in 1810/11 and Mary unearthed the body one year later.

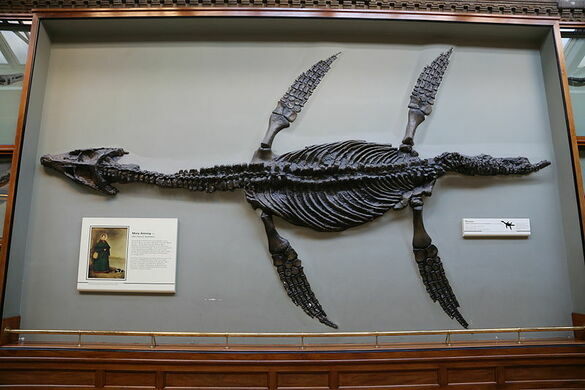

Anning found the first complete British Plesiosaurus giganteus which became the type specimen. She found the fossil under Black Venn cliff and shared a sketch and details of the find in a letter to William Buckland in 1824. Buckland was a geologist and scholar who became Professor of Geology at Oxford in 1818 and he and Anning developed a good relationship.

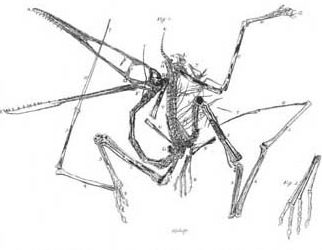

Another significant find was the first example of the winged pterosaur, Pteradactylus macronyx (renamed Dimorphodon macronyx). She shared the find with Buckland who identified it referencing Georges Cuvier’s work. Buckland bought Anning’s specimen, and the British Museum of Natural History in London later bought it in 1835 (Lyme Regis Museum, 2017).

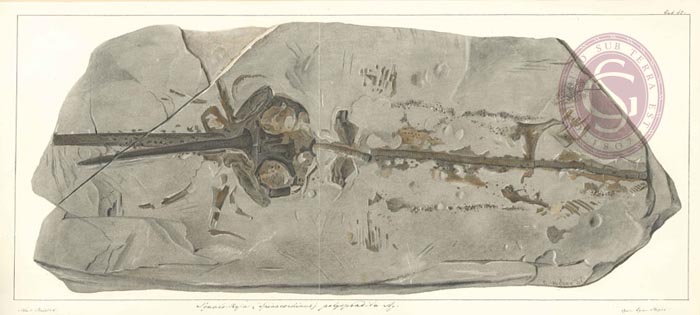

Anning also found the first example of a new genus of fish, Squaloraja, which also became a type specimen. Pierce (2013) reveals that when Anning found the Squaloraja, experts claimed it was a ray. However, Anning dissected a modern ray to discover they were different: she had found another new species. Anning found the fossil but Louis Agassiz wrote about the fossil in Recherches sur les Poissons Fossiles (1833-1843). He commissioned a watercolour of the fossil to include in his book. The original specimen was destroyed during World War Two, but the tail survives in the Philpot collection now at Oxford University Museum of Natural History.

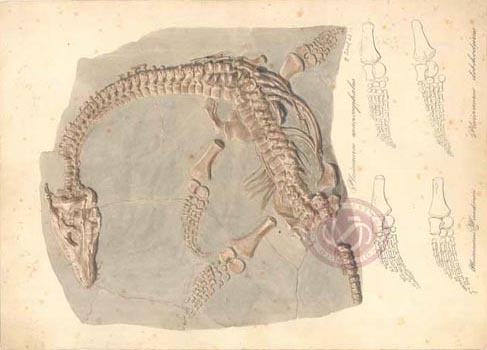

Anning shared her finding of the Plesiosaurus macrocephalus in a letter to Buckland on 21 December 1830. It was named by Buckland, and bought by Lord Cole (Enniskillen) for 200 guineas. In 1883 the Enniskillen collection went to the Natural History Museum where it can be seen today.

Anning spent her life finding fossils, and sharing her knowledge and finds with scholars like Buckland, Henry De La Beche, William Conybeare, Roderick Impey Murchison, Adam Sedgwick, Gideon Mantell, Charles Lyell, Thomas Hawkins, and Richard Owen.

She died of cancer in 1847. In her lifetime, she was not fully recognised for the significant role she played. For example, many of the finds she made were named after someone else. However, Pierce highlights some key fossils that did honour Anning. “It was the Swiss Louis Agassiz who finally established some justice for Mary, but not until 1841, when he named a fish, the species Acrodus anningiae, after her. He named another species of fish Belenostomus [Belonorhychus] anningiae in 1844. However, there were no such acknowledgements by British colleagues in her lifetime.”

In 1878, R.F. Tomes named a new liassic coral genus and species Tricycloseris anningi. In 1936, L.R. Cox named the bivalve genus Anningia, although this had to be changed in 1958 to Anningella. In 1927, Robert Broom named the Karroo reptile genus Anningia and in 1932 this became the core for a new order, the Anningiamorpa. In 1969, Alan Lord named a new ostracod species Cytherelloidea anningi.

In 1846 in the Minute Books of the Geological Society, the entry for 2 July reads: ‘Resolved that Miss Mary Anning and [another] be requested to become Honorary Members of the Institution.’ In the year after her death, De La Beche addressed the Geological Society and honoured the lives of those Fellows who had died in the past year, as was the custom. His friend Anning was included, even though she was not a Fellow. This was the first time a woman had been acknowledged this way, since women were not accepted as Fellows of the Geological Society until 1904, almost sixty years after Mary Anning’s death.

Anning was an extraordinary woman who was a gifted palaeontologist, fossil finder, and fossil dealer. Her findings have contributed to scientific knowledge of both the Jurassic period as well as the history of the earth. It is only after her death, however, that she gained the recognition and acknowledgement that she deserved for her groundbreaking work.

References

Atlas Obscura. (2018). Mary Anning’s Pleisosaur. https://www.atlasobscura.com/places/mary-annings-plesiosaur

Lyme Regis Museum. (2017). Dimorphodon And the Reverend George Howman – Mary Anning, William Buckland and ‘Pterodactylus’’ Macronyx. https://www.lymeregismuseum.co.uk/Related-Article/Dimorphodon-Reverend-George-Howman-Mary-Anning-William-Buckland-Pterodactylus-Macronyx/

Museum of Natural History. (2018). Mary Anning’s Ichthyosaur. https://oumnh.ox.ac.uk/Mary-Annings-Ichthyosaur

Pierce, P. (2013). Jurassic Mary: Mary Anning and the Primeval Monsters. The History Press.

The Geological Society. (2014). Mary Anning (1799-1847). https://www.geolsoc.org.uk/Library-And-Information-Services/Exhibitions/Women-And-Geology/Mary-Anning

The Geological Society. (2014). ‘Squalo-Raja (Spinacorhinus) Polyspondila Agassiz’, [1834-1836]. https://www.geolsoc.org.uk/Library-And-Information-Services/Exhibitions/Women-And-Geology/Mary-Anning/Squaloraja

The Geological Society. (2012). Watercolour of a Plesiosaurus Macrocephalus, [1838]. https://www.geolsoc.org.uk/Library-And-Information-Services/Exhibitions/Women-And-Geology/Mary-Anning/Watercolour-Of-A-Plesiosaurus-Macrocephalus